この計画では、旧塚本家主屋、旧丸林家土蔵という2つの建造物を保存改修し、藍染・竹細工・手漉き和紙をテーマにした3つの客室と、宿泊の受付的な役割を果たすうなぎBOOKS、以上の4つのデザインを担当した(以下、詳細ページへのリンク)。

1_ 旧塚本家主屋|藍の部屋

2_ 旧塚本家主屋|竹の部屋

3_ 旧丸林家土蔵|和紙の部屋

4_ うなぎBOOKS

Process

Product

この計画に合わせて、地域のつくり手といくつかのプロダクトをデザインした。地域に受け継がれてきた伝統技術と、現代的な都市生活をつながりを再発見するための試み。

6_場の痕跡を織り込んだ絣

7_竹編のランプシェード/テーブル

Text

八女福島の伝統的建造物保存地区にある建築を改修し、宿泊施設へと転用するプロジェクト。クライアントである「UNAラボラトリーズ」は、物・人を媒介にした地域文化の継承を目指し、ショップを運営している福岡県八女市にある地域文化商社「うなぎの寝床」と、歴史的建築物の活用を起点にその土地の歴史文化資産を尊重したエリアマネジメントと持続可能なビジネスを実践してきたシンクタンク「リ・パブリック」が共同でつくったトラベル・デザイン・ファームである。

この宿は、クライアントがこれまでの過程で出会った人や技術、知恵、文化を、体験的に知ってもらう場であるが、宿として独立した存在でなく、これまでの活動の延長線上にある場であり、そのためのツアーや紙媒体も用意されている。これまでの『商品を見る/買う』という関わり方に加えて、宿泊体験を通して『商品を感じる/体験する』ことができるようになるため、商品の良さを体験的に知ってもらうことができる。

このプロジェクトでは、宿泊することで体験者の意識が地域文化に向かう状態をつくることを目指している。この宿で過ごす中で、地域文化や職人の手わざを五感で感じることができる状態をどのようにしたら実現できるか、という視点を軸に、全体からディテールまでのデザインを考えた。

「職人の手わざに視線を向かわせるために、我々設計者の手わざを消した」といえば、逆説的であるし、やや極端ではあるが、わかりやすい技術の露出ではなく、出来上がった形ができる限りアノニマスなものになることを目指した。ぱっと目をひくものではなく、いつ、だれが、どこでデザインしたものかわからない。無国籍でタイムレスであるが、使う度に職人技の粋を感じることができるもの。職人たちとの対話を重ねる中で、そういうものをつくるには、これまでのデザイナーや職人のやり方とは逆のプロセスが必要だと気が付いた。デザイナーが新しい理想の形を提示し、それを職人が形にする、というプロセスではなく、職人がつくりたいと思うものを現代にローカライズするためのチューニングをデザイナーが行う、というプロセスである。むやみやたらに新しい形をつくるのではなく、何世紀も引き継がれ、愛されてきた形や技術を踏襲しながら、現代の空気やニーズにフィットさせるための試行錯誤をひたすら繰り返す作業であった。古き良きものと新しいものの狭間を探るものづくりである。

また、もう一つ大切にしたのは、古き良き日本の生活を単に再現するのではなく、現代的な営みの風景に馴染ませることで「生きた景観としての宿泊体験」を実現する、ということである。非日常や遠い過去への郷愁、礼賛を味わう場所ではなく、たとえ都心のマンション暮らしであっても、持ち帰って自分の生活や日常に取り入れることができる。日常と地続きにある体験を提供する場が、この宿が目指す姿である。

伝統的建築物の改修は建築当初の姿に戻すことを目指すのが常であるが、形だけの街並みが残っているのではなく、人の営みを受け入れながら残っていくことを目指す場合は、「古きを活かしながら、いまのニーズに合わせてローカライズする」ことが必要であると考えている。将来、文化財として残すこともできるよう、可逆的であることが前提とされる伝統的建築物保存のルールの中で、宿という現代的な機能に置き換える作業が求められた。

ここでも「古き良き生活の風景を、いかに現在の風景に馴染ませていくか」、という視点を軸にデザインを考えた。どこからが新しくどこからが古いのか、一目では境目がわからないが、よく見たらわかる、という状態を敢えてつくっている。デザインするというよりも、境目を馴染ませる作業をした、というのが正解のように思う。

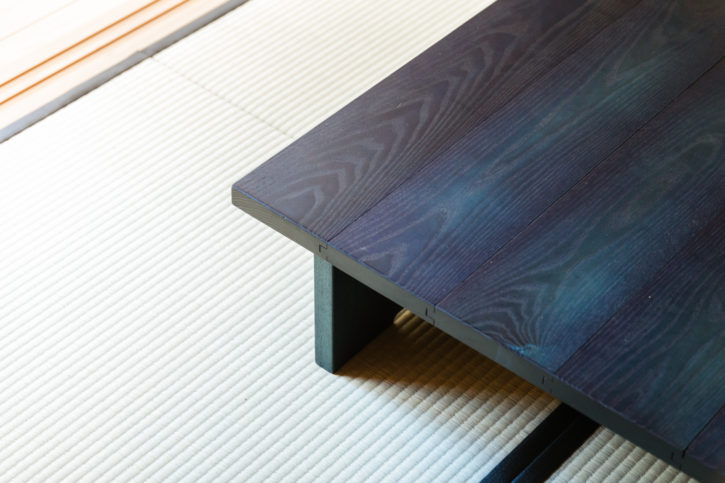

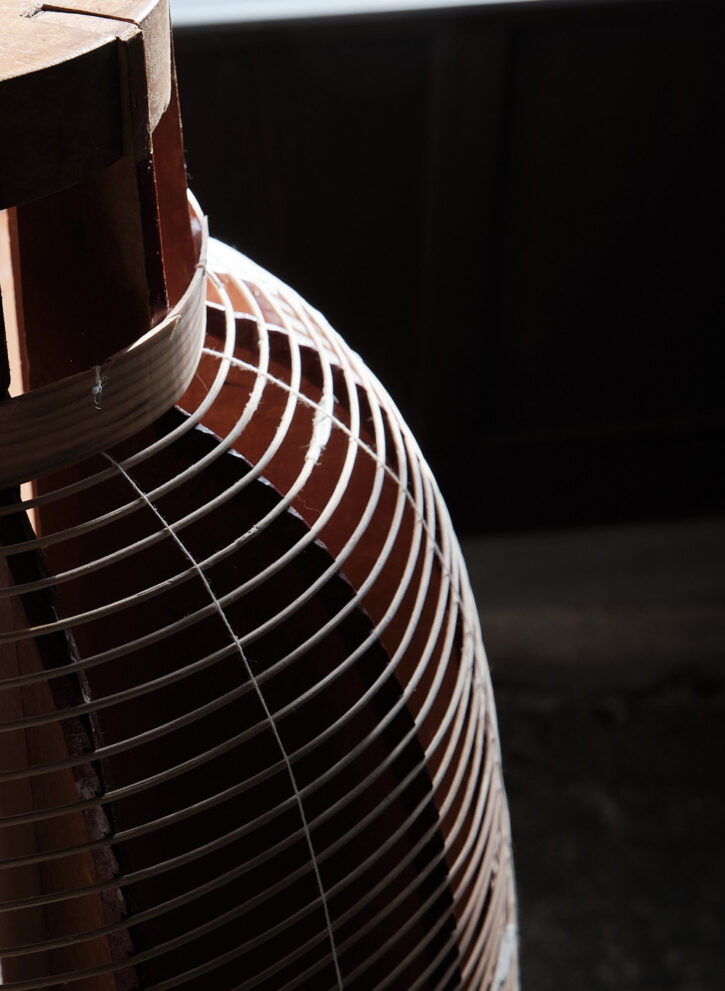

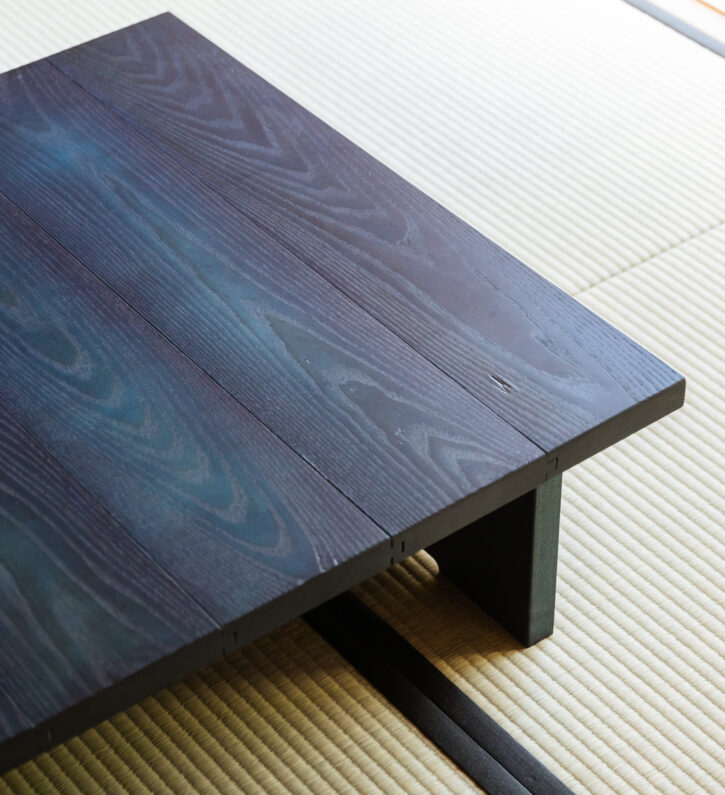

また、今回のプロジェクトでは、一部の家具や建具のデザインや製作にも携わっている。先染めして組み立てた蓼藍(タデアイ)のローテーブルや、竹網の天板と足を籐で編んだローテーブルなどがそれである。家具は通常、分業でつくられたパーツを集めて一か所で組み上げる工程でつくられるが、今回のプロジェクトでは、デザインする側の我々と同様、それぞれのパーツの職人たち自らが全体の製作プロセスに関わっている。職人たちによる新しいアイデアが、これまでできなかったことを可能にし、技術の粋が詰まった美しい家具の創出に繋がったと考えている。

ーーーー

The project was to renovate a building in the historic district of Yame Fukushima and repurpose it into an inn.

The client for the project was a travel design firm known as UNA Laboratories, an organization devised and created in collaboration between UNAGINO-NEDOKO (a Yame-based shop-owner and trading company aiming to preserve regional culture, intermediating between the people of the region and its products) and RE:Public (a think tank engaged in the practice of better area management through the repurposing of historically protected buildings as sites for sustainable businesses that honor their local history and culture).

The inn, in the process of meeting with the client, had become a place where you could interact with the local people, hear their wisdom, and learn about their crafts and culture, but it was still unable to operate on its own as an inn. At this point, it only functioned as an extension of an idea by providing a hub for tours and a space for informational brochures. If it were to become a place not simply for perusing and buying local goods, but a place where you could actually feel and experience these goods during an overnight stay, you might come away knowing more intimately—through experience—that they are well-made.

The project called for an experience that would put guests in a heightened state of attentiveness to the regional culture. But how to create such conditions? How might you create an experience where you can stay and feel the culture of the region and the handcraft of its artisans in all five of your senses? We thought in order to draw attention towards the technique of the artisans, we should draw attention away from our own technique. Perhaps that’s counterintuitive or a little extreme, but we wanted designs that didn’t show their hands, something that would feel as anonymous as possible. Not spaces that would catch your eye, but ones that would render you unable to tell where, or when, or by whom they were designed. Timeless and without a nationality—where every stay you would feel the essence of the makers’ craftwork.

Upon many discussions with the artisans, we came to the realization that, if we were to ensure such a thing, we had to do the exact opposite of what we had always done. Not a process where the designers’ ideals would be molded into form by the artisans. A process where what the artisans’ pieces could be fine-tuned and modernized by the designers.

Our job was not to thoughtlessly launch ourselves into making something new. We stuck to the beloved shapes and tried-and-true techniques passed down through the generations, working intently—through repeated trial and error—to suit them to the needs and sensibilities of the present day.

What we made is the product of our exploration of the interstitial spaces between old and new.

One more important thing we did to make living the scenery a reality was to create a landscape that would blend more with modern ways of living, rather than simply recreate the old Japanese way of life. So not a place that would glorify nostalgia for a strange and distant past. An experience that even a city-dweller living in a condo could take with them and implement it into their everyday life. That is what the inn intends in its form: a place providing an experience that stretches back into the everyday.

It’s common practice when renovating traditional buildings to try to restore them to the way they once were. In our minds, it wasn’t just about leaving the townscape as it had been—we also needed to ensure that we could modernize this facility so it would continue accommodating the needs of those in charge of it.

To ensure it would remain a cultural asset into the future, It was requested that we refurbish it to function as a modern day inn, under the premise that this could be undone if needed, as per historic building preservation rules.

In this aspect as well, we looked at it through the lens of how might we blend scenes of the old life into scenes of modern life?

You may not be able to tell at a glance where the old ends and the new begins, but if you look closely, you can find out. That’s the state we wanted to put people in. Rather than call it design, it might be more accurate to say we were blurring lines.

Lastly, this project had us engaged in the design and production of some furniture and fixtures—a low table dyed with indigo, a bamboo wicker tabletop woven with rattan into its white ash wooden frame. Typically for furniture, we have a process of sourcing pre-made parts and assembling them on site, but for this project, the craftsmen were involved in the design side, making various components for us from scratch. Thanks to their ideas, we were able to do things we couldn’t have done before. We think that led to the creation of some beautiful furniture that feels alive with the spirit of their touch.

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|藍の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_indigo-725x483.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|和紙の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_washi_1-725x685.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|竹の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_bamboo-725x483.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/te-725x483.jpg)