漉きこまれた過去の痕跡.

Identity.

photo ©️ Koichiro Fujimoto

photograph by Koichiro Fujimoto

和紙の原料のひとつである梶の木の栽培から一枚の紙ができるまでの全ての工程を一貫して製作している「名尾手すき和紙」は、佐賀県佐賀市大和町にある300年の歴史を持つ老舗の工房である。昭和初期には100軒ほど和紙工房が存在していたが、徐々に減少し、現在は名尾手すき和紙工房が最後の一軒となり、谷口一家がその技を受け継いでいる。

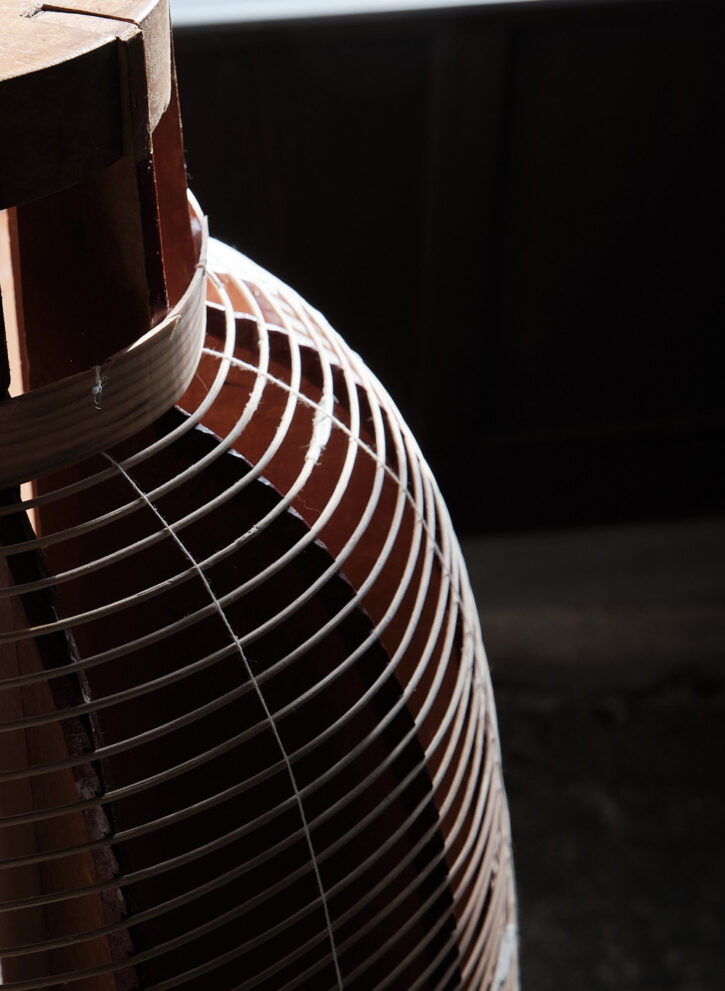

今回のプロジェクトでは、改装前に残されていた襖の中から出てきた古紙や、蔵の壁の下地に使用されていた名藁縄を漉き込んだ新しい和紙を作り、障子紙や提灯を包む和紙などとして使用している。この、「場の痕跡が漉き込まれた和紙」は、7代目の谷口弦さんが近年注力している「昔の紙を粉砕して漉きなおし、現代の還魂紙(かんこんし)を作る」という取組みの思想を出発点に生まれたものである。

材料|現場に残っていた古い襖紙、和紙

製作|谷口弦(名尾和紙)

Process

乾燥させた梶の木を水に浸す.

それを綿状にしたものが和紙と原料となる.

建築当時の藁縄.

大切に回収した角頭の釘, 明治期になり丸頭の西洋釘が輸入される前から存在した, 時代の痕跡.

Text

「還魂紙(かんこんし)」とは、原料の入手や製作に手間がかかることから、紙が大変な貴重品だった時代に作られていた再生紙である。使い古しの紙を細かく粉砕した後、一旦水に晒して液状にし、それを再び漉き直すという手法で作られていた。近年、谷口さんは、この日本独自の再生紙文化をヒントに、物語を持つ素材を混ぜることで生まれる和紙のあり方の可能性を模索している。「現代の還魂紙を」と語る谷口さんのつくる和紙を用いて、単なる「紙」という存在を越えて、「場の記憶を引き継いだ新しい場の創出」を象徴する状況を生み出すことができるのではないか、と考えた。

旧塚本家では、改修前の襖に残されていた、可愛らしい手書きの模様が施された襖紙や、断熱材の代わりに入れられていたと思われる、うつわ店を営んでいた時代の帳簿などの切れ端を使って新しい和紙を作り、提灯や障子紙として利用している。当時の生活を偲ばせる味わいと美しさを備えたこの古紙を使って、幾重にも漉くことによって出来上がった和紙には、奥行き感と、古紙の透け具合による濃淡が生まれた。光を通すと、まるで和紙の星空を見ているような風景が立ち現れる。

旧丸林本家土蔵の内壁には、土壁の下地があらわしのまま残っており、藁縄を丁寧に編み込んだ手技の痕跡が、テクスチャーとして美しかった。ここに使用している和紙には、土壁を更新する際にほどいた古い藁縄を細かく粉砕したものを漉きこんでいる。長い間壁を支え続けた藁縄は、本棚の土台やアートピース、提灯を包む和紙に生まれ変わって、優しいあかりで来訪者を出迎える。

Vestige Washi Paper / The Vestiges of a Former Place, Pressed into Washi Paper

Nao Tesuki Washi is a factory that has been operating for over three hundred years in the Yamato district of Saga City, Japan. The shop is engaged in the entire process of making traditional Japanese paper by hand, from the material sourcing of mulberry tree fibers to its eventual pressing into sheets of paper. Today, Nao Tesuki Washi is the only such shop remaining. The Taniguchi family, who own and run the shop, carry on the legacy of these techniques.

For this project, we took materials from before the renovation—old paper from the sliding doors and ropes that were used to tie together the bamboo framework inside the walls, and pressed these materials into a new paper. Then we was used this new paper for the shoji panels and the lantern at the entrance.

Pressed into that paper, are the vestiges of a former place.

In recent years, Ken Taniguchi, seventh generation in this long line of washi paper makers, has committed himself to a process in which decades-old paper is pulverized into a new composite. He’s recycling it, or as they say, he’s reviving it. That’s the thought process that informed our approach.

Kankonshi was a means of recycling used paper in an age when it was a precious commodity. In those times, getting the materials for making paper took a lot of time and effort. It’s a process wherein old, used paper gets crushed into fine bits, which are then soaked into a pulp and repressed into new paper. Literally put, it’s paper whose soul has been restored.

Taniguchi, inspired by this unique culture of Japanese paper recycling, has spent the past years trying to figure out how washi might be made by mixing in materials with a story to tell. In his mind, kankonshi goes beyond mere paper into something more symbolic. “Modern day kankonshi,” Taniguchi said, “is about making a new place that inherits the memories of a former place.”

Back before the renovation, the space still had its old paper doors. The doors were stuffed with paper that was sprinkled in these quaint scribblings, likely as a makeshift insulation. We took those scraps—including account books from when the place operated as a shop selling dish-wares—and used them for the paper in the lanterns and shoji panels.

That old paper, so reminiscent of the beauty and elegance of that old life, was pressed over and over into new washi. It has a depth to it, its history speckled against the transparency of the shoji panels. When the light shines through, a beautiful scene materializes before you. It’s like gazing into a paper night sky.

The exposed earth of the Marubayashi House’s inner walls give it some beautiful texture. As does the straw rope once so carefully woven to support its walls.There is washi in this room that has been pressed together with the fine pulp of the old ropes we untethered to rebuild its walls. Those ropes, having long supported these walls, have been given a new life. Now they live in the base of the bookshelf, the art framed on the wall, and the paper of the lantern hanging outside, which welcomes guests with its gentle light.

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|藍の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_indigo-725x483.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|和紙の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_washi_1-725x685.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|竹の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_bamboo-725x483.jpg)