ペンダント照明.

フロアスタンド.

ブラケット照明.

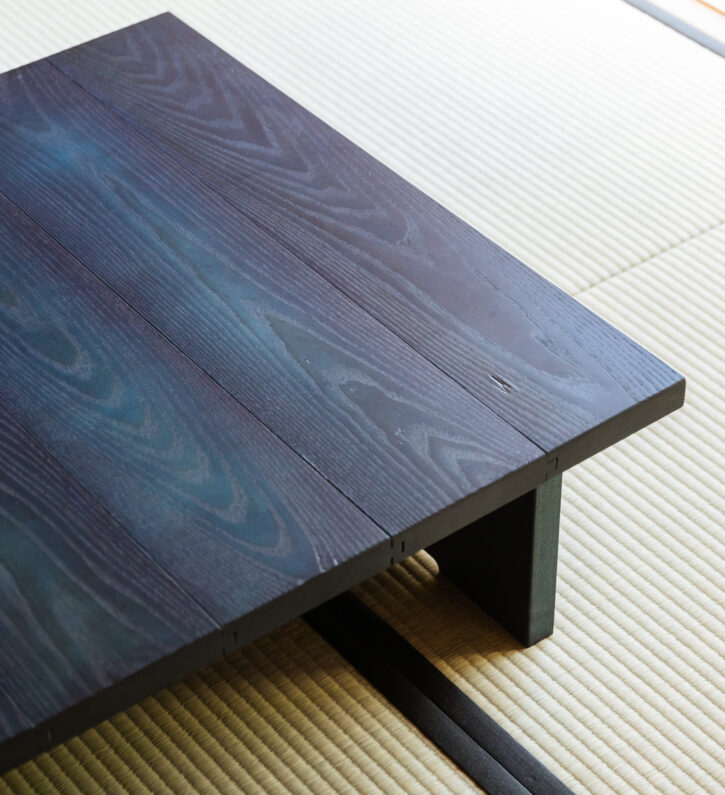

藍の部屋 / 寝室

和紙の部屋 / リビング

Photograph by Koichiro Fujimoto

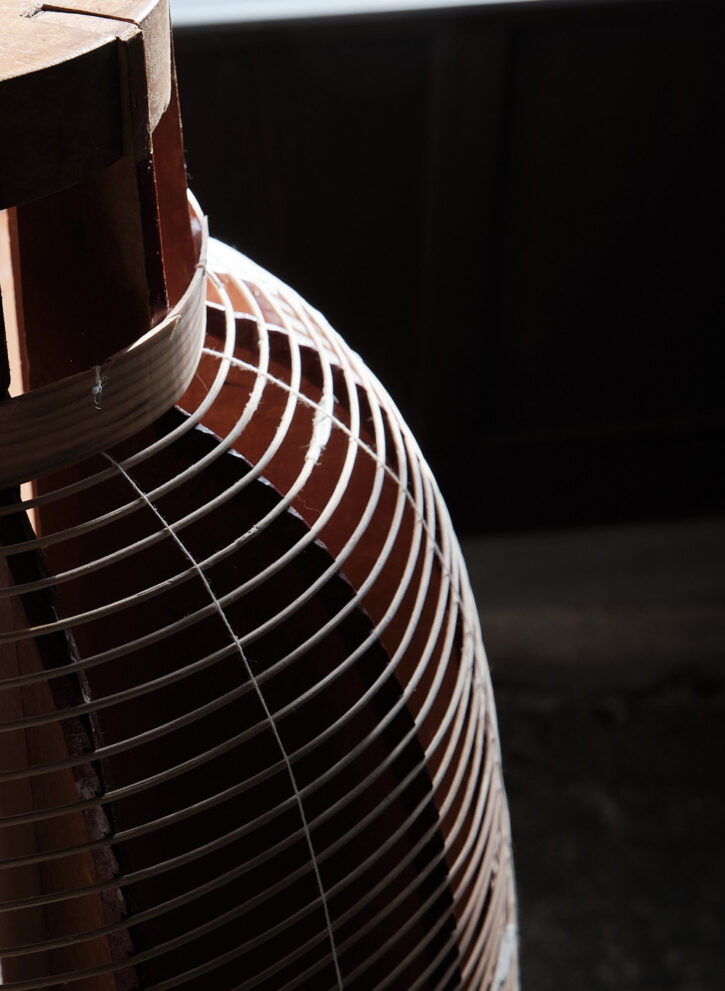

「伊藤権次郎商店」は、福岡県八女市に工房を構える1815年創業の提灯屋である。八女提灯は、一本の細い竹ひごを提灯の型に沿って螺旋状に巻く「一条螺旋式」が特徴で、火袋には薄紙の八女手漉き和紙を用いることから内部が透けるため「涼み提灯」とも称され全国的に名声を博している。ファッションビルのプロモーションの仕事を経て、家業を受け継いだ8代目の伊藤博紀さんは、現在、平日は八女で提灯をつくり、週末は都市部に拠点を移し生活する、という日々を過ごしている。その行為からも、伝統と革新との距離感を測っているようにも感じる。

今回のプロジェクトでは、伝統的な提灯の持つ曲線の美しさをそのまま活かした照明の在り方を考え、旧塚本家、旧丸林本家蔵それぞれに使用している。初めて工房を訪れた際、デザイン案を携えた上で臨んだが、結局デザイン案を伊藤さんに見せることはなかった。対話を重ねる中で、私たちが率先して新しい造形を描く必要がないと感じたからだ。

材料|竹ひご、和紙

製作|伊藤博紀(伊藤権次郎商店)

Process

提灯の骨組みの造形は、木型に竹ひごを巻いて成形していく。そのため、新しい形の提灯を作るには、新たな木型から用意する必要がある。「江戸時代から約300年かけて生み出され受け継がれてきた造形には、残ったなりの意味を感じる。そこに敬意を払い、生き残ってきた美しさや造形を守り続けながら現代に合うもの考えたい」、という伊藤さんの伝統文化や文脈に対する意識を、現代の生活に馴染むものに落とし込んでいくにはどうしたらよいか、ということを軸にして、提灯が出来上がってきた歴史や文脈の延長線上にある「新しさ」をつくりたいと考えた。

八女提灯の形はよく見ると、下に向かってほんの少し細くなっている。縁起物としてそこに文字が描かれることを前提とした提灯は、その文字が天に登っているように見えるように、そのような造形になっているという。いままでそのように意識したことはなかったが、提灯を提灯たらしめている造形の特徴やアイデンディティは提灯下部の曲線にあるのではないかと思う。この造形をそのままランプシェードにしたいと考え、既存の木型の中から現代の生活の中でも使いやすいサイズのものをセレクトし、ひっくり返してバランスを見ながら竹ひごの巻きを止める位置(提灯を切断する位置)を決めていき、最終的に8種類の照明を作った。

Yame Lantern Light

Ito Gonjiro Shoten is a shop in Yame, Fukuoka which has been making paper lanterns since 1815. What makes a Yame paper lantern special is how a singular bamboo strip is spiraled around to form its skeletal structure, as well as the thin, wafery paper wrapped around that structure—making it appear transparent when lit. For this reason, many throughout the country refer to these lanterns as “open air lanterns.” Hiroki Ito, eighth generation heir to his family business, carries on its legacy in the present day by working to promote fashion boutiques. He spends his weekdays making paper lanterns in Yame, spending his weekends moving them downtown. In this act as well, he walks the line between tradition and innovation.

In this project, we considered how we might create lighting fixtures that would showcase the beautiful curvature of these traditional lanterns. They are used throughout both the Tsukamoto and Marubayashi houses.

The first time we visited the lantern workshop, we had some designs in hand, which we planned to propose to Mr. Ito. In the end, however, we never did. The reason being that, through our talks with him, we felt convinced there’d be no need for us to take the lead in designing a new shape.

The skeletal structure of these paper lanterns is formed by wrapping a bamboo strip around a wooden spine.Thus, making an entirely new shape would have necessitated preparing a whole new wooden spine.

“It means something,” Ito told us, “that this structure has withstood the test of time for roughly three hundred years since the Edo period. We should be honoring that. Let’s think about something that continues to preserve the beauty and shape that has survived to this point, but in a modern way.” We thought about how we might make something suited to present day life that was nonetheless imbued with Ito’s cultural sensitivity and contextual awareness. With that as our guiding principle, we endeavored to create something new that extended naturally from the historical context in which these lanterns were made.

Ito said that if you look closely at a Yame paper lantern, you’ll see it narrows toward the bottom. It’s said to be shaped that way because whenever words are painted on the paper—like a talisman—the symbols look like wishes floating up to heaven . That’s when it dawned on us that perhaps the real defining characteristic of a paper lantern—its true identity—lies in that curve toward the bottom.

We devised to take this structure as is—fashioning it into lampshades. From the components of wooden spines readily available in the shop, we selected sizes that would suit modern day living. We turned them over, studied their balance, and decided the locations of the cut-off point for the bamboo strip (i.e. the edge of the lantern). In the end, we made eight types of light fixtures.

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|藍の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_indigo-725x483.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|和紙の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_washi_1-725x685.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|竹の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_bamboo-725x483.jpg)