Photograph by Koichi Torimura

八女で地元の土を使い、釉薬の研究を行いながら独自の器づくりを行う「風見窯」の杉田貴亮さんと一緒につくったのが、八女土のレンガタイルである。

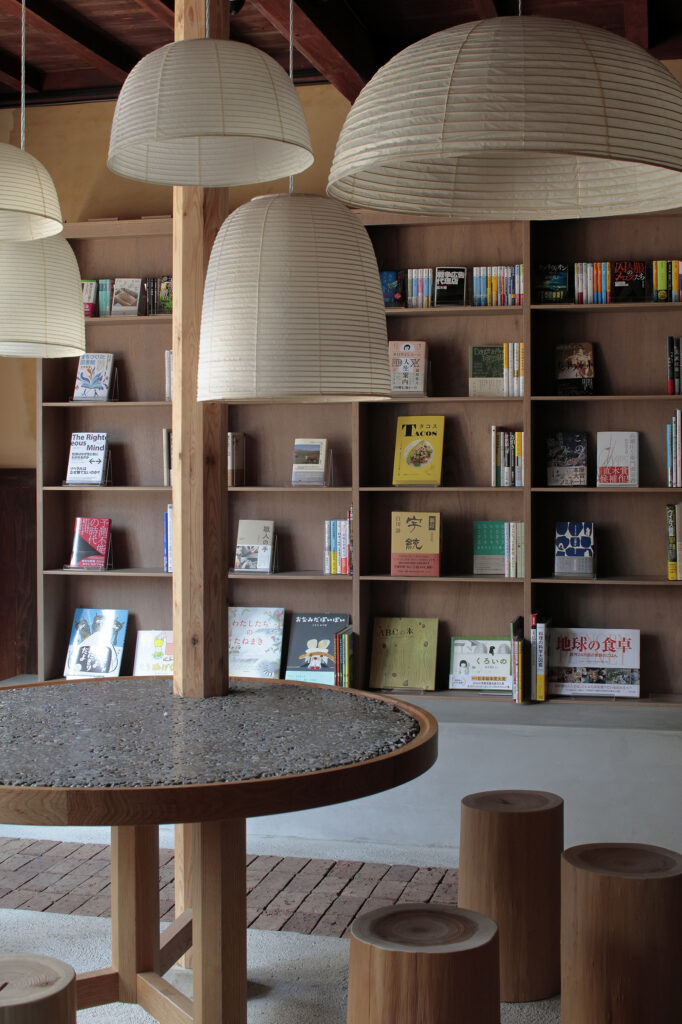

「八女土のレンガタイル」とは、その名の通り八女の土をそのまま固めて焼いたレンガタイルである。本棚の前の通路に敷き詰めたこのレンガは、さりげないが独特の存在感を放っている。敢えて遺物を除かず、土をそのまま陶土として焼き上げたレンガタイルの無骨な表情は、この土地らしさや力強さが凝縮しているようにも見える。

材料|八女土

製作|杉田貴亮(風見窯)

Process

当時, 杉田さんが作陶に使用していた登り窯.

地域からいただいた土を大切に利用している.

土を水に浸し, 時間をかけて不純物や砕石を取り除く.

限られた陶土層から粘土をとるのではなく, 地域の資源を有効利用するための知恵.

杉田さんは地元の土で陶土を精製し、地元で採れた藁灰を原料とした釉薬などをつかい器をつくっている。工場で調達した素材を使うだけではなく、その土地のものにしか生み出せない表現や美しさを追求し、その方法に帰結している。

今回のプロジェクトでは、ただ単純に八女の土を敷き詰めて土間にするなどではなく、

人の手を介して製品になった建材を使いたかったため、杉田さんに相談したところ、地元の素材を使って建材を作ってみたいと思っていたそうで、目指す方向が期せずして一致した。

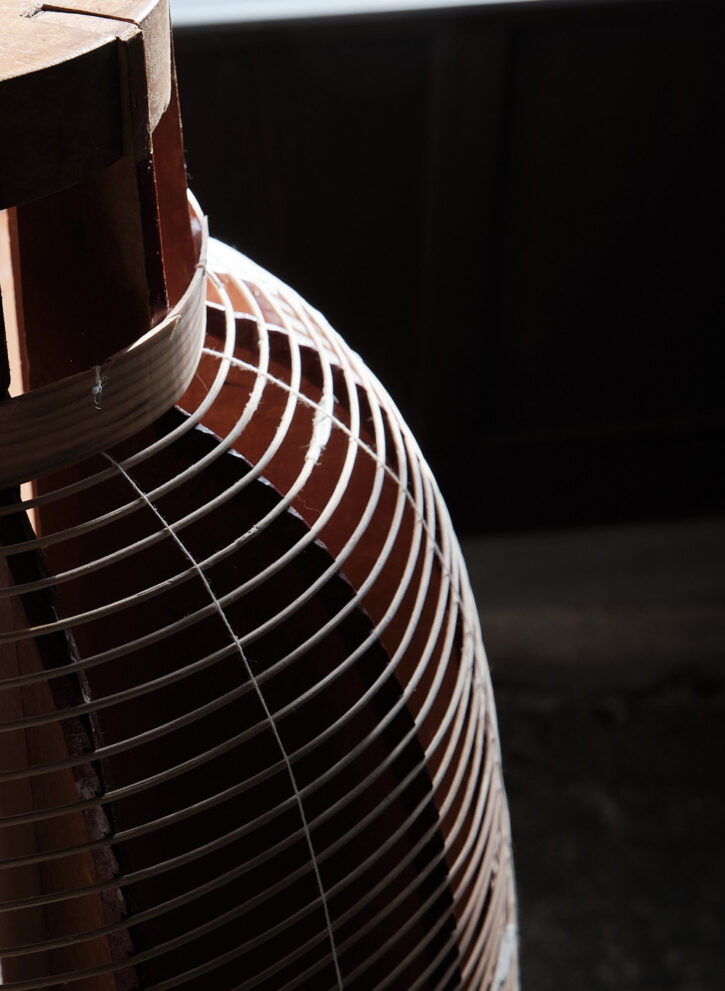

まずは地元の土で効率よくレンガタイルを作るためには、寸法と、どの温度で焼くかを決める必要があった。通常の焼き物では陶土で造形を作り、乾かした後に700度くらいで素焼きをし、絵付けや釉薬をかけたあとに1300度くらいで本焼をするが、建材であるため一般の人でも入手可能な価値にするには、合理性やコストも考える必要がある。登り窯で焼くため、効率的に焼けるよう焼きの工程は一度にし、焼くときにのせる板のサイズを考え、歩留まりの良い寸法にしなければならなかった。

はじめには素焼きの700度で焼いてみたが強度が出なかった。本焼きに近い1100~1200度度で焼いてみたところ、十分な強度は出たのだが、溶けきれずに残ったガラス質が表目に滲み出していた。はじめは失敗作と思ったが、ずっと眺めていると、それが味のように感じられるようになった。手間をかけて作ったものではあるが、不要なものがそぎ落とされて製品になる前の、材料と製品との間のように思えた。そこでさらに、石などの遺物を取り除いた土と、遺物を取り除かない土の両方で陶土を作り、同条件で焼いてみたのだが、遺物を取りのぞかない土の方に、豊かな表情が現れた。土地ごと窯に入れて焼き固めたような、そんな印象だ。

掘り出したそのままの八女の土を、ガラス質を残した状態で焼き上げる焼き方が、この土地の表情を表現するのに一番良い方法だとたどり着いた。

Brick Tiles of Yame Earth

These brick tiles of Yame earth were made in collaboration with Takaaki Sugita of Kazamigama, a pottery workshop engaged in researching the process and materials of ceramic glazing while crafting its own earthenware.

As the name suggests, this is the unrefined soil of Yame, packed and baked into tiles of brick. Laid out in the hallway before the bookshelf, they exude a presence that is unassuming yet unique.

These rustic-looking brick tiles, baked with minerals deliberately left remaining in the clay, give the appearance of the strength and essence of this land, compacted.

The earthenware Takaaki Sugita makes is truly local—he refines the clay taken from the ground beneath him and bakes it into earthenware using the ashes of locally harvested straw as fuel.

His workshop is not simply concerned with utilizing its own provisions—it seeks to express a particular kind of beauty that can be realized nowhere else. This is the resulting process.

For this project, we didn’t want to simply just do an exposed earth floor for the entryway—we wanted to use building materials that could act as their own piece as a proxy for the craftsmen’s touch. Upon consulting with Mr. Sugita about this concept, it turns out he had already been wanting to try making his own building materials. So as it turned out, we were already set on the same path.

Sourcing the local earth and making that into brick tiles efficiently would require deciding measurements, as well as at what temperature to bake the clay. For regular ceramics, after forming the clay into shape and letting it dry, you first bake it at around 700 degrees, then you glaze it and fire it at 1300 degrees. But since these are building materials, you have to consider what is reasonable and cost effective in order to make it an accessible to everyone. For an efficient one-time process, we devised to bake the clay in what’s known as a climbing kiln, which is built on a slope. So we had to consider the size of the slope and what dimensions would give the best yield.

First we tried baking the clay at 700 degrees, but it would not harden adequately. After heat the kiln at a temperature closer to what’s reserved for after glazing (between 1100 and 1200 degrees), the clay was hard enough, but this caused a glass-like substance to seep out onto the clay’s surface and harden there. At first we considered this a failure, but after looking at it longer, we got a feel for its charm. Here we had taken so much time to make this thing, and in the moments before we scraped off the part we didn’t need, it seemed to hover somewhere between material and product.

From there we continued baking more of this clay—some with traces of pebbles and things removed from the soil, and others with them left in. We baked these two types of clay under the same conditions, and what we found was that the clay with the pebbles left in was so much richer in its features. It gave the impression of plots of earth which had been hardened in a kiln.

In the end, we arrived at the conclusion that the best way to represent the true face of this land was to leave the Yame earth just as we dug it out, with those glassy fragments baked in.

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|藍の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_indigo-725x483.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|和紙の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_washi_1-725x685.jpg)

![Craft Inn 手 [té]|竹の部屋](https://rhythmdesign.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/craft.inn_.te_bamboo-725x483.jpg)